Building a Crypto Trading Bot from Scratch - 3: Abstract Base Classes

One of the questions I kept asking myself while building this trading bot was: “How do I make this flexible enough to add new strategies and exchanges without rewriting half the codebase every time?”

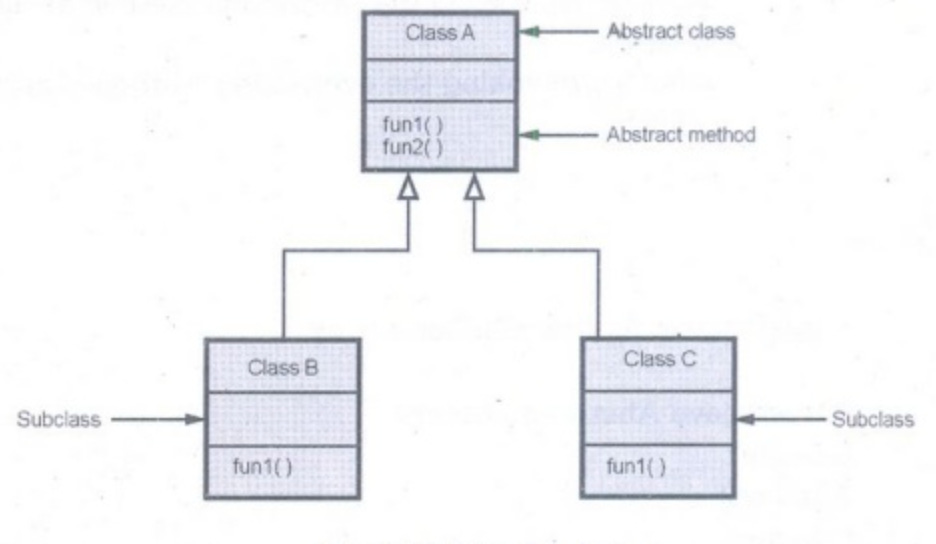

The answer turned out to be one of those object-oriented programming concepts that sounds academic until you actually need it: abstract base classes (ABCs).

In this post, I’m going to show you two critical abstractions in my system—BaseStrategy and ExchangeBase—and why they’re the secret sauce that makes the whole thing extensible.

The Problem: Every Strategy Is Different

When you’re building a trading system, you quickly realize that not all strategies are the same.

An EMA crossover strategy is completely different from an RSI oscillator strategy. A machine learning strategy would be different still. They use different indicators, different logic, different parameters.

But they all need to do the same fundamental thing: take market data in, produce trading signals out.

So how do you design a system that supports any strategy you might dream up in the future, without having each strategy be a tangled mess of custom code?

This is where abstract base classes come in.

BaseStrategy: The Contract for All Strategies

Here’s the core idea: define an abstract base class that specifies what every strategy must implement, but leaves the specific logic up to each strategy.

In Python, that looks like this:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from typing import Dict, Any, List

from src.models.candle import Candle

from src.models.signal import Signal

class BaseStrategy(ABC):

“”“

Abstract base class for all trading strategies.

All custom strategies must inherit from this class.

“”“

def __init__(self, config: Dict[str, Any]):

self.config = config

self.name = config.get(’name’, self.__class__.__name__)

self.symbol = config.get(’symbol’)

self.timeframe = config.get(’timeframe’)

self.parameters = config.get(’parameters’, {})

self.risk = config.get(’risk’, {})

# Validation

if not self.symbol:

raise ValueError(”Strategy config must include ‘symbol’”)

if not self.timeframe:

raise ValueError(”Strategy config must include ‘timeframe’”)

@abstractmethod

def generate_signal(self, candles: List[Candle]) -> Signal:

“”“

Analyze market data and generate a trading signal.

This is the core method that implements strategy logic.

Must be implemented by every strategy.

“”“

pass

@abstractmethod

def calculate_position_size(self, signal: Signal, account_balance: float) -> float:

“”“

Calculate position size based on risk parameters.

Must be implemented by every strategy.

“”“

pass

Let me break down what’s happening here and why it matters.

The @abstractmethod Decorator

The @abstractmethod decorator marks methods that must be implemented by any class that inherits from BaseStrategy.

If you try to create a strategy without implementing these methods, Python will raise an error:

class IncompleteStrategy(BaseStrategy):

pass

# This will fail:

strategy = IncompleteStrategy(config)

# TypeError: Can’t instantiate abstract class IncompleteStrategy with abstract methods generate_signal, calculate_position_size

This is huge. It means you can’t accidentally create a strategy that’s missing critical functionality. The type system enforces the contract.

What Every Strategy Must Do

Looking at BaseStrategy, there are two methods every strategy must implement:

1. generate_signal(candles) -> Signal

This is where your strategy logic lives. Give it a list of historical candles, and it returns a trading signal (BUY, SELL, or HOLD).

The beauty of this abstraction is that the Strategy Engine doesn’t care how you generate that signal. EMA crossover? RSI thresholds? Machine learning? Doesn’t matter. As long as you return a valid Signal object, the system works.

2. calculate_position_size(signal, account_balance) -> float

Different strategies might want different position sizing logic. Maybe you risk a fixed percentage of your account. Maybe you use Kelly criterion. Maybe you adjust size based on signal strength.

By making this an abstract method, each strategy can implement its own position sizing logic.

Shared Functionality: The Best of Both Worlds

Abstract base classes aren’t just about forcing implementations. They can also provide shared functionality that every strategy gets for free.

For example, I added these concrete (non-abstract) methods to BaseStrategy:

def validate_signal(self, signal: Signal) -> bool:

“”“Validate that a signal meets basic requirements.”“”

if signal is None:

return False

if not 0.0 <= signal.strength <= 1.0:

return False

if signal.symbol != self.symbol:

return False

return True

def get_stop_loss(self, entry_price: float) -> float:

“”“Calculate stop loss price based on entry price.”“”

stop_loss_pct = self.risk.get(’stop_loss_pct’, 2.0)

return entry_price * (1 - stop_loss_pct / 100)

def get_take_profit(self, entry_price: float) -> float:

“”“Calculate take profit price based on entry price.”“”

take_profit_pct = self.risk.get(’take_profit_pct’, 5.0)

return entry_price * (1 + take_profit_pct / 100)

These methods provide default behavior. Every strategy inherits them automatically. But if a strategy needs custom logic, it can override them.

This is the power of inheritance: common functionality in the base class, unique functionality in derived classes.

A Real Strategy: EMA Crossover

Let me show you what a real strategy looks like when inheriting from BaseStrategy. Here’s a simplified version of my EMA crossover strategy: